Alex Tattersall: Thoughts on minimizing environmental impact

Underwater Macro Photography

Thoughts and strategies for minimizing our environmental impact

By Alex Tattersall.

Digital underwater photography is still in its infancy yet along with the rapid advances in social media, the wealth of impressive underwater images is now breath-taking. By signing up to some of the numerous UW photography groups on social media networks, very quickly you will be exposed to a seemingly endless stream of simply stunning imagery. Furthermore, we need only to follow the development of UW competition winning images over the last ten years to appreciate how far the art has come in such a relatively short time.

Unfortunately, this makes creating original and innovative imagery an increasing challenge, and in our small, obsessive world where many people want to develop a stand-out profile to self-promote and perhaps build an income stream, the challenges are obvious. If money is no object (or they are assigned on a professional budget), photographers can travel to relatively unchartered territories to find rarely photographed species in unusual topographical locations. Others choose to take their cameras deeper for new and interesting scientific revelations and fauna encounters. Most of us though will look to capture unusual behaviors or new perspectives on frequently photographed species hoping to create stand out images to gain kudos among our peers.

Anyone who has travelled to some of the world’s macro hotspots cannot fail to notice the ‘pointy stick’ that has become the norm wherein small macro subjects are corralled and positioned into more photogenic poses and locations in order to produce more attractive photos. Subjects are herded into couples/triplets/cross species encounters, or even towards potential predators in order to present behavioral situations that will earn their photographer the competition prizes/respect/kudos they desire.

Note well- I must say here that I have also been involved in such practice which at the time seemed to be the norm and a part of my earlier portfolio can be attributed to such critter manipulation. It is important also to note that I was largely driven through aspiration to replicate the successful images of my seniors, many of which had been achieved through similar practice. I was also admittedly driven to producing original shots to build my own industry profile.

The issue of drawing the line with critter manipulation is an ethical dilemma and each photographer will be guided by his or her own evolving personal code of ethics. Ethics are generally formed around norms, peer behavior and opinion, and respected spheres of influence. However, it seems that as the wealth of amazing imagery increases, we are seeing some photographers resort to more and more extreme measures in their quest for originality. The good news is that there is a resounding movement in the UW world now gaining momentum against such practice and spheres of influence such as respected photographers, resort owners, dive guides, competition organisers and magazine editors are being lobbied to assist in policing dubious practice.

Fashions change of course as do what is understood as acceptable and unacceptable practice. It was not long ago that we saw series after series of benthic octopi being photographed from below parachuting out of the water column. Some such images won prestigious competitions, setting the trend for a multitude of imitators. Learning and aspiring photographers see winning images and want to emulate them. If the ethical practice of how the winning images were shot is seen as the norm, as key influencers, competition organizer, judges and winning competitors are perhaps inadvertently setting up the next generation of photographers for ecological failure. The same is true, if not more so, for the increasing number of UW photo workshop leaders whose images inspire and whose techniques and practice educate.

Having been involved quite heavily in the debate of critter manipulating, during my most recent workshop trip to Dumaguete, Philippines, I consciously put aside my ‘bothering rod’, using it only to stabilize myself and turned my attention to photographic techniques rather than critter manipulation to attempt to produce a portfolio of original and interesting images. I’d like to share some of these here with you now to give ideas of how to minimize our impact as photographers on our environment (addendum- having sat down to pull together images, I realize that some of the images from previous Lembeh and Puerto Galera trips demonstrate the techniques equally well).

Backgrounds

The beauty of the UW macro world is that even on the most hardcore of muck sites, there are outcrops of beauty which can be used as attractive negative space. Something as simple as a seapen, urchin or a crinoid can play host to numerous fascinating subjects. Many of these backgrounds do not respond well to being poked, polyps retracting, crinoid arms waving or urchins fleeing, therefore far better images can come from a hands-off, gentle and careful approach.

An example is the triplefin goby. These skittish subjects have a habit of flitting away and then returning to the same place of rest. Some choose bare and unattractive rock, others choose more photogenic backgrounds. Fish such as these are skittish at first but become used to relaxed diver presence after time. A long macro lens is invaluable however, and a pointer stick will have an undesired affect on this species (i.e. it will swim away rapidly).

The triplefin goby was ubiquitous in Dumaguete and the numerous specimens came to rest in a variety of places. The blue tunicates proved to be a much nicer background than the rocky outcrops

In this second image, frogfish big and small were everywhere in Dumaguete. This very attractive yellow juvenile was much more reflective than the dark, volcanic substrate. Behind, a slice of mango peel had been thrown from the boat and was being eaten by a spiky, black urchin. This mango color complimented the frogfish and offered an interesting background. Again, no poking required.

Crinoids can make the most wonderful textured and patterned negative space and play host to some fascinating creatures. As soon as the crinoid is disturbed, its movements will make capturing a good shot far more onerous, the best shots will almost inevitably come as a result of zero physical contact with either crinoid or critter.

Having a small sized compact camera in this case was a major advantage for approaching and framing this usually skittish subject. Minimizing contact with the host critter makes life so much easier for the photographer.

So, begin your search for these backgrounds, know they are there and exploit the photo opportunities they offer passively and conscientiously and the rewards will come to you.

Magnification

If an interesting subject is framed against an unattractive background, a strategy to eliminate this is to use high magnification. This will have the effect of either filling the frame with the features of your subject, or creating a narrower depth of field that will effectively blur out any unattractive rock or substrate negative space. The first example is the Christmas Tree Worm. This is a subject, I’m sure you know, that will retract rapidly into its hole should it feel excessive vibration in the water column. A pointer stick is of no use here! It is therefore a very good subject to hone photography skills, to move gently with controlled breathing, to demonstrate good buoyancy and to be very gentle in approach. Once these skills are finely tuned, you will find that you become a far more effective macro photographer, subjects will be less intimidated by your presence and will be more welcoming of your advances.

Tiger shrimp seem to be very much an ‘en vogue’ subject currently but we see these more and more photographed perched beautifully atop seemingly unnatural but stunningly contrasting backgrounds such as blue tunicates against a black water column. We also see them photographed flying through the water column with eggs in their abdomen. I have only rarely seen a tiger shrimp and it was neither perched on a blue tunicate (as if it were fully aware of the color wheel and how nicely orange can contrast with blue), nor free-swimming in the water column. When I have seen them, they have, like boxer (pom-pom) crabs and harlequin shrimp, been on a sandy or rocky substrate. Rather than corral them into position with a pointer stick, try increasing magnification as in the image here which blurs the background and still offers an impressive image.

The hairy squat lobster usually sits quite inaccessibly in the folds of large barrel sponges, not easy to approach and certainly not easy to introduce strobe light as the barrel sponge folds often block this. With supermacro diopters and a very steady approach, if you choose the right non-skittish subject (a player as we call them), magnification can produce an interesting image while avoiding unattractive negative space.

For all these shots, the technique is in the approach. Set up your strobe output prior to approaching the animal using a similarly reflective colored surface. Consider your desired depth of field before making the approach. Set the camera to rear button focus and focus on a rock beforehand. Approach with very little exhalation of bubbles, carefully, slowly and smoothly. If the critter decides it doesn’t want you in its comfort zone, just let it go and find a more cooperative specimen. Above all, respect and look in wonder at the animal and avoid prodding it back into an accessible place with a steel rod. Discourage your guide from doing the same if necessary.

Lighting techniques – inward lighting, snoot lighting

As photographers, we have the ability to light what we choose to light. My first example demonstrates the effectiveness of inward lighting. A lovely pinkish seahorse was curled around a seapen in a sheltered sandy dip on the ocean floor during a high current dive. I took a couple of shots and quickly realized the sandy background was distracting (you can see this in the image below). In order to isolate the seahorse from the sandy background without interfering with the subject, I turned the strobes inwards pointing them towards the camera and tried again. The result was a subtly lit seahorse with no distracting background. There was no need to move the seahorse into a better position, simply through a more controlled strobe position, I was able to get the shot I wanted with no physical disturbance of the subject.

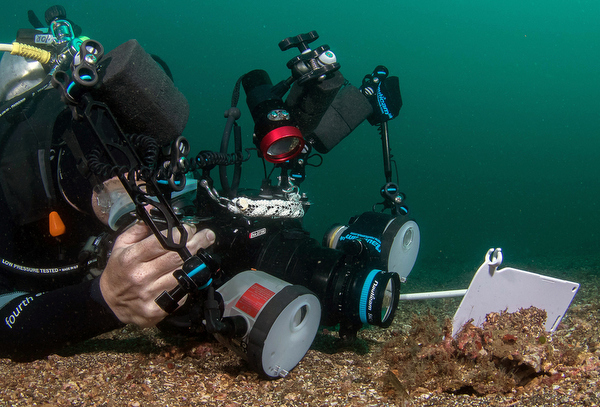

Snoots and focused light are an excellent way of removing unattractive backgrounds and seem to have little effect on many species of marine life if used with care and attention. If you are shooting alone, the ideal practice I’ve found (with some early guidance from Alex M I should mention) is to find a subject and then consider the size/power/definition of the light I want to produce. If the snoot or light shaping device has options of light point size, I can make this decision early. I will then find a rock or patch of similar size and reflective property/color to the subject in order to set up the shot before approaching the critter. With the snoot attached to a strobe on two long arm (1x 300mm and 1x 200mm usually) segments on the left side of the housing, I can physically move the light into position, pull the focus using the rear lever and practice a couple of shots. If the light point is too large or too powerful/weak, I can make these adjustments before approaching the subject.

Once set up in this way, I tighten all the clamps on the arm so the arm is rigid and then make my approach. Once the subject falls into focus, I know that the light is in approximately the right position; a few minor adjustments and the light can be placed where I want it. Some devices use the strobe’s spotting light as a useful aiming tool, others recently have developed a red laser pointer (visible even during the day – very useful). Through lack of understanding as to the effects of laser pointer light on critters’ eyes, I set the laser to be a couple of millimeters away from the subject itself although I may have been worrying unnecessarily. The result of careful light placement is that you can take original and beautiful images with minimal impact to the marine environment.

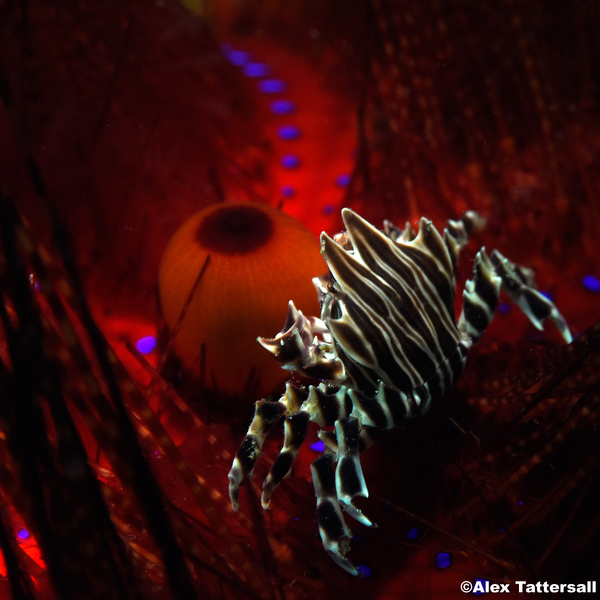

Zebra crabs, as I’ve seen, move around the urchin quite actively and seem to feed of the urchin’s waste product among other things. Poking these special subjects with a pointer stick will cause them to bed down or scurry away and the fire urchin will also usually start moving at considerable speed away from perceived threat. Contact again is undesirable. The snoot light allowed focus on the crab’s carapace and highlighted the colors of the fire urchin trails.

These older images of seapen polyps in Sogod Bay, the Philippines, demonstrate how a directed light source can take a subject and make it into something special.

These are an older sequence of photos but I think they demonstrate the effectiveness of targeted light in removing unappealing backgrounds and producing stand-out images. No need for a pointer stick here either, the polyps would certainly retract into the seapen if touched.

Naturally occurring behaviors

Animals do things, don’t they? They eat, sleep, spawn, yawn, fight, even flirt. These behaviors make for amazing and outstanding photos. In the recent debates about critter manipulation, concern was repeatedly expressed about what happens if a one in a million behavioral sequence occurs and competition judges deem it to be manipulated or a social media witch hunt ensues. This is a very real concern currently and it is certainly not our intention to encourage that we ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’, as we say in colloquial English. Anyone capturing unique and amazing behavior would surely stand firm in their knowledge and not fear reprimand from their peers. I know I certainly would. Many behaviors though cannot be manipulated, and are indeed sometimes actually easier to capture as the subjects are distracted by their activity.

Here I was trying to capture behaviors that could under no circumstances be attributed to pointer stick interference.

This image demonstrates the importance of approach. With the camera and lens combination I was using, working distance was much less than it would have been with the 105mm macro lens on the DSLR. Having setup for the shot with all strobe and camera settings tested on a benign surface, I was able to use a very slow and steady approach to this small cardinalfish. Each time it seemed it would swim away, I stopped and moved back slightly as it became more and more comfortable with my presence. The animal always had the option to swim away and the shots I took were very limited.

A commotion in the weeds and suddenly I saw this epic battle going on between two very small scorpionfish. The battle continued for 15 minutes and both animals were seemingly oblivious to my presence. Natural behavior with no intervention from the photographer.

25 minutes with this lovely sea snake, every 5 minutes or so she would go to the surface to breathe. At first she seemed wary but then let me follow her up each time for that magical reflective moment.

Depth of field and blur

At the fingertips of any photographer (with a camera which allows manual settings) is the ability to open the aperture and blur distracting surroundings. Blurred areas are rendered stylistically differently depending on the main lens and supplementary wet diopter make-up. Rather than move a critter into a more photogenic setting, we have the option of using blur to our advantage, effectively making the subject pop out of the image.

All too often do we see blue ringed octopi isolated against the water column in unnatural seeming locations. Try using shallow depth of field to isolate the critter in its natural environment if it decides to stay near unattractive benthos.

This juvenile filefish was hiding in an unattractive setting, simply by reducing depth of field by increasing aperture size, I was able to blur the background to a uniform sandy color which resulted in a complementary color to the other features in the image. No manipulation of subject position required.

Be aware of course that opening the camera aperture and not reducing ISO requires a decrease in your strobe light output to keep the same exposure. When using such shallow depth of field and open aperture, flash power is usually nearly minimum. Strobe effect on critters will often come up in the debate regarding affecting our environment so minimizing output may cause fewer disturbances. The only methodical empirical testing study I have seen is that of David Harasti with seahorses which doubts negative effect on the subjects tested. As sensitive photographers though, we all surely know when a subject has had enough of us and our activity, we all must have felt this and responded appropriately.

Placing backgrounds

Once upon a time, a number of beautiful nudibranchs were relocated to an underwater studio which showed the animals impressively set against white backgrounds. This series of photos was quite groundbreaking at the time and was widely published and of high profile. This unfortunately made it seminal in numerous mimicry projects. We have touched earlier on how accepted practice changes over time but I think this demonstrates the importance of role models and successful imagery in forming the next generation of photographers. In the quest for originality and renown, photographers think up more creative methods, with greater or lesser impact on the environment and the subject. It is possible though to present a critter against an alternative background with minimal impact to the environment. Here I have taken a simple dive slate and placed it behind the subjects.

Gently placing the white slate behind the subjects allows separation with minimal interference.

This flabellina nudibranch detail framed against white makes an interesting hi-key image without the need for any contact with the subject.

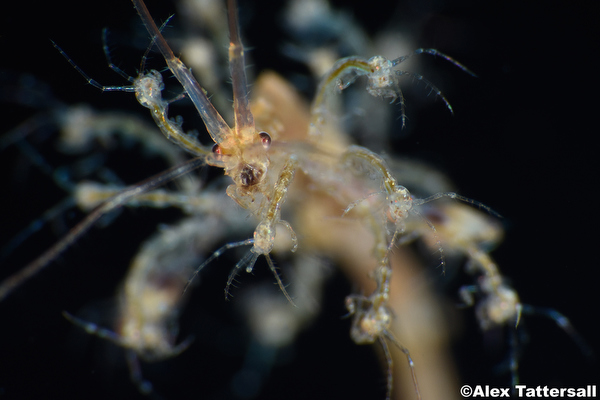

Dumaguete proved to be a real hotbed for the curiously macabre skeleton shrimp and during our visit there this month they were absolutely everywhere, many of them with young clinging on to their backs. Testing a new diopter prototype, I took several shots of an individual with young against the sandy substrate. After a short while, I considered whether the impact of a black background would make for a stronger image and so unscrewed and gently placed another wet diopter I had on my dual flip holder just behind the subject. The images show the difference. I didn’t need to lift the subject into the water column to obtain the black background, a practice I’ve seen frequently and admittedly done myself in the quest for more outstanding images.

Backgrounds, mirrors, matts can be used responsibly to produce good images but can also be used carelessly to the detriment of the welfare of the marine environment. As people want to mimic certain photo styles, being transparent with the way the images have been produced seems to me to be the best hope to prevent abuse and misuse.

It is my hope that the above six strategies may find their way into many of your photographic toolkits and consciousness when you are ‘in the zone’ with a cooperative subject. I intend to continue and develop this article as new ideas are shared in the UW photo community. The ideas presented above were not formed in a vacuum, they were developed from experiences and sharing of ideas with other passionate members of our community. Much of the inspiration for this article comes from the comments made by divers and UW photographers in our online petition for change in UW macro photo practice. You can find this here and are very welcome to add any ideas you think would be helpful and browse the comments of others.

To conclude, we all have in common a love for the marine environment and being immersed in this watery world. As UW photographers, we have already developed a poor reputation among non-photographic divers for our single mindedness (and sometimes recklessness) when behind the camera. There is also risk of perceived entitlement over subjects and ego can intervene. Our interaction with the marine environment is less passive than non-photographic divers and we collectively need to be aware of this. However, as one poignant comment on the petition above points out, it is far easier to be tolerant of one’s own behavior than the behavior of others, so change unequivocally needs to start with ourselves.

It is a very human desire to stand out, to be counted and to be respected by our peers. It is also unfortunately very human to want to amass financial reward and indeed a survival requirement for many of us. However, it seems that ambition and the quest for photographic originality, kudos and status in our community is making many of us lose sight of why we original fell in love with the aquatic environment in the first place. To be passionate wildlife photographers at the expense of the wellbeing of our subjects is the ultimate irony and sadness.

Addendum

This article attempts to consider some of the issues in the underwater macro photography experience. I am well aware of similar ethical questions concerning large animals, baiting of sharks for example, and the emotion this causes to many of us. If another photographer would care to take the baton on this topic, that would be interesting, as this really falls outside of my own experience. I am also aware of the practiced arguments against us that there are more important things going on in the world. This unquestionably does not make our concern about the direction in which current underwater macro photography is headed any less valid.

About the author:

Dr. Alex Tattersall is a well-known and award winning underwater photographer and owner of both Underwater Visions and Nauticam UK, Ireland and France. He has become an outspoken advocate of minimizing photographers’ impact on macro subjects.

All views are those of the author and not of Wetpixel LLC or its agents.