Douglas Seifert’s illustrated notes from the field: Part 4

A Digression:

I have been around a while, visited a lot of interesting and not-so interesting places in my time and have encountered the wonderful, the strange and even the outright mystifying. I have learned a few things, and this “Jetties of South Australia” Expedition™ reiterated one of the lessons I had taken for granted, namely: People living in small country towns or on islands or peninsulas often exhibit the lamentable syndrome of insularity, which is defined as ignorance of- or being uninterested in- other people or cultures outside their experience.

As one raised in the southern United States, from an early age, I was brought into contact with small-minded rednecks, smug religious fanatics, rascists, sexists, and general ignoramuses of many flavors over the years and took for granted that such boorishness was restricted to North America.

I was startlingly disabused of this notion by some of the landlubbers utilizing Port Hughes Jetty for their recreational fishing activities. A man accompanied by his young daughter walked out to the end of the jetty, near where our boat was at anchor. He carried two fishing rods, one for him and ostensibly one for his daughter, who he appeared to be teaching to fish. It would have be an admirable scene, a man spending time with his daughter and teaching her a skill, but his bright t-shirt bore the wording “Rope a Slope” bordered by a stylized rope noose. We had to ask our cook Jo what that meant, since it wasn’t exactly clear and Australian slang has a life all its own. Apparently it is a horribly rascist rallying cry for some segment of the Australian population that seeks to keep Asian immigrants from seeking asylum or applying for citizenship. In short, this t-shirt, which not subtle in the slightest (if we could read it from more than 50 feet away), was a walking advertisement for what in many places would be called a Hate Crime. Doubtless the daughter was being taught more than fishing (racism is a learned behavior not necessarily inherent in our makeup).

Our group was disturbed and dismayed by this encounter (didn’t other people on the Jetty also find this slogan horrific?) and were further disenchanted by the local fishing community when a rotund, middle-aged man accompanied by a similarly troglodyte companion carried very large fishing rods to the end of the Jetty and began dedicated shark fishing. As a board member of Shark Savers and as a conservationist, enlightened naturalist and journalist, I am appalled by senseless sport fishing for sharks, where the animal is killed not for food, just as a bloodsport pastime. This fisherman was not interested in catch and release, which, although personally I feel is a waste of time, is far preferable to wanton, pointless slaughter. He just wanted to kill sharks, all sharks, as if to compensate for having to live with his own small tackle.

While we were diving, one of the passersby on the Jetty told our crew that a four meter great white shark had been spotted near the Jetty the previous week. We were told of this bit of local information between dives. Was it true?, we wondered. Was a great white shark in the area currently, was there really, truly one seen a few days prior, or was this the local embellishment meant to scare outsiders/tourists/hated divers? Divers are always blamed by fishermen for poor catches “because the divers scare away the fish” or some variation on that theme.

We decided it was the local boogeyman story (its always a “four meter white pointer” seen at the jetty recently in every small Australian country town) and continued our dives although admittedly as visibility declined and clouds darkened the seascape, the creepiness factor was ratcheted up.

January 2014 – South Australia

Some of our fellow passengers were chomping at the bit because had never seen a leafy sea dragon. This was not surprising since this fascinating species, large and ornate cousin to sea horses and pipefish, lives exclusively along the coasts of South Australia and the south coast of Western Australia and can be seen nowhere else in the world except at a few public aquariums. Port Hughes Jetty, wonderful as it is underwater, simply does not have the types of seagrasses and kelp leafy sea dragons favor, so we would have to move along to our next location.

But before we departed, it was time for a night dive. The world beneath the jetties comes alive at night as invertebrates vacate their shelter and hidey-holes to hunt and mate under cover of darkness. The bottom was alive with blue ringed octopus crawling upon the substrate. Shrimp and crabs had emerged from the sand and were foraging. The shrimp, transfixed by light from the dive torches froze in place; the crabs raised their claws to defend themselves as they scuttled away sideways from the light.

Carey furiously waved his light to get our attention and we were rewarded with a sighting of a beautiful, red hued, long-armed octopus making its way the border between sand and seagrass. It was a Southern Sand Octopus (Octopus berrima), an infrequently seen cephalopod that burrows in the sand by day and is active nocturnally. The find was quite serendipitous as Carey had only seen this species five times in over 1500 jetty dives. The octopus was not impressed with our lights and firing strobes and endeavored to bury itself in the sand so we left it to its inclination, eventually.

We surfaced from the night dive at close to midnight but the excitement and adrenaline kept us wide awake for hours as we discussed this dive and others over celebratory beverages and the boat weighed anchor for the ten hour journey to Edithburgh Jetty.

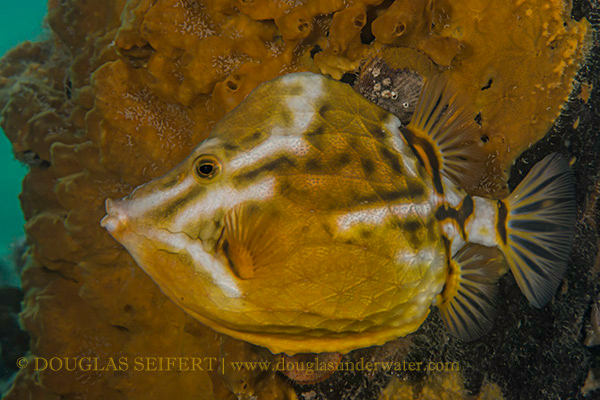

We arrived the next morning to Edithburgh. Since it was the middle of the week, it was quiet, not crowded with fishermen or other divers. I had dived Edithburgh Jetty a few years previously and had then encountered wonderful cold-water marine life in the rubble on the bottom in the shade below and at every twist and turn around each support pylon. The pylons are heavily encrusted with invertebrate growth and attract all manner of predators and grazers: frogfish, nudibranchs, stargazers, and other macro marvels. It is considered one of the premiere dives in Australia and its vast, nearby seagrass beds are a favored haunt of leafy sea dragons.

Our first dive in was a shock. The once heavily encrusted pylons looked sparse, sickly. It was no trick of memory, but instead environmental treachery by non-thinking government bunglers. It was quickly ascertained that a few weeks before, at the beginning of December, 2013, fifty-two of the wooden support pylons, home to innumerable animals, had been removed, without consultation, by the Yorke Peninsula District Council Department of Planning, Transport, and Infrastructure, under the excuse/justification of “public safety” but with a complete disregard for the marine environment itself, fishermen or divers. The result is an marine habitat that looks as ravaged as where on land a hurricane meets a shoreline: the underwater equivalent of strip mining. Inexcusable short-sightedness by politicians who have zero interest in conservation or protecting the unique living marine heritage of South Australia. The shame of a nation and a cautionary tale for us all.

In hours of searching, not a single member of the three species of frogfish commonly seen under Edithburgh Jetty could be found. Nudibranchs were few and far between. There were many, many blue ringed octopus (again) and more species of fish that the recreational anglers found appealing.

There are people that will claim that the encrusting animals will grow back in a couple of years as if that makes it okay to eradicate wholesale entire populations. What that “few years” excuse does not address is that for many animals that live less than a year under the best of circumstances, it will be generations before numbers can rebound if they rebound at all.

Since the Jetty was in such a sad state, it was decided to search for leafy sea dragons in earnest. The visibility was less than ten meters, but relatively clear due to the strong sunshine.

The seagrasses were like underwater forests, giving shelter to a vast collection of marine species: pipefish, short-snouted seahorses, a giant cuttlefish, crabs, and small swarming clouds of mysid shrimp – the preferred prey of leafy sea dragons.

We sent Carey, Andrew, divemaster exceptional Mike Ward and Our World Underwater Rolex Scholar Chloe Marechal to survey every area of the seagrass savannahs. Joining the search were guests Lupo and Greg, and after an hour and a half, they began to return to the boat, one by one, having covered a lot of territory but having no luck in finding the elusive sea dragons. Morale diminished as each team member relayed their lack of success in finding dragons and indicating which part of the shoreline they had covered. Just as hope seemed lost, Carey returned to the boat with good news: he had found two leafy sea dragons; an adult male and a small Young of Year juvenile. As soon as air tanks were refilled, team members took turns to visit the leafies and to make still photographs and moving image sequences.

Leafy sea dragons are damning creatures, like all sygnathids. They respond to a perceived threat, in this case a hulking, bubble-blowing behemoth floating in its immediate vicinity and maneuvering a glass domed, metal box with bright flashing or continuous lights towards the sea dragon, by an enigmatic non-confrontation technique of turning away from the threat and showing its tail instead of its face: the aquatic equivalent of an ostrich burying its head in the sand? The result is a frustrating circling dance where a diver swims in tight circles trying to get ahead of the sea dragon and the dragon making even tighter circles to make that shot impossible. From a distance, it is pretty hilarious to observe. As the photographer trying to get that head-on shot, the bubbles exhausted from the regulator are a heady mix of carbon dioxide exhalation and a creatively linked stream of profanity, blasphemy and maledictions.

But, if given time and space, sea dragons can get used to the diver with a camera and do settle right down, ignoring a diver’s intrusion into the dragons comfort zone/sphere of personal space. With a few images successfully achieved, the dragons were left to their camouflaged lives among the kelp and sea grasses and the intrusion of divers was short in duration and hopefully non-stressful to the animals.

As the late afternoon skies darkened, we readied for the night dive. My personal goal for returning to South Australian Jetties for this expedition was to see and photograph a Striped Pyjama Squid (Sepioloidea lineolata). These cephalopods are also known as dumpling squid, and like bobtail and bottletail squid, are actually more closely related to cuttlefish than squid. They are nocturnally active, spending daylight hours beneath the sand with only their eyes occasionally visible but by night they rise above the sand when hunting, or remain only slightly submerged in the sand, their eyes and some of their sand-covered mantle more easily seen with a diver’s torch.

Carey led the way and it was not five minutes into the dive when he indicated Striped Pyjama Squid everywhere! Not only one, not two, but ten, twenty, more. Sometimes they were close together, sometimes singly, some completely exposed above the sand, some just a pair of white eyeballs appearing like a pair of white marbles above the sand, but there were Pyjama Squid everywhere and for me, the expedition was a success on all fronts. The guests had seen amazing creatures found nowhere else, especially the iconic leafy sea dragon, and I had fulfilled my ambition to see and photograph another interesting member of the cephalopod family.

I even had a terrific amount of luck late into the dive when Carey signalled me and pointed out a pair of Striped Pyjama Squid locked in an embrace of mating! But you will have to look for that image in an upcoming issue of DIVE Magazine…