Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: Orcas in Antarctica

Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: Hunting Orcas Swim Down a Newly Opened Lead in the Ice

For my second column entry featuring my favorite images from my career, I wanted to share some images from Antarctica.

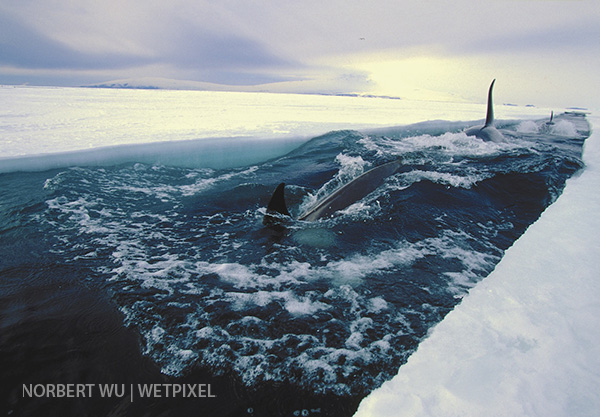

This image shows a pod of orcas (killer whales) (Orcinus orca), swimming down a narrow lead in the ice that just opened up a few minutes before. Here are captions from some magazines and books about this image:

In McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, the austral summer arrives each January accompanied by the sound of cracking ice and the sight of hunting orcas. Bombarded by four months of continuous sunlight, the sea ice that once covered 7 million square miles, shrinks to a mere 1 million square miles. And as the ice breaks up, orcas prowl the newly formed edges for prey ranging from Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) and penguins to the giant Antarctic cod, or Disosstochis mawsoni.

“I’ve watched large groups of orcas work one area of the ice edge, diving repeatedly down and under the sea ice,” says Jim Mastro, an expert on Antarctic marine life. “They can’t get deep enough into the ice to stand much of a chance to get Weddell seals … but we do know that there are mawsoni hanging out under the fast ice, and there is no bigger, juicier treat than one of them.”

As air breathing mammals, these killer whales are taking considerable risks to get food. The ice channels and holes they explore can close up within minutes, leaving them trapped without access to the surface. Sometimes, the whales will rest within small pools of open water for hours, waiting for the ice around them to clear so that they can swim back to the open ocean. Other times, a pod will spy hop from an ice hole apparently looking for a safe route back to open water.

While the orcas hunt for their prey, scientists like Mastro also risk the shifting ice floes to study the orcas. Helicoptered in from the McMurdo Station research base some 20 miles away, teams take advantage of walk-up access to get tissues samples, take photos and even dive with the orcas.”

Well, the above caption is a typical caption in a magazine where editors, and not writers or photographers, control and edit the content. One thing I’ve learned over the years is that the media almost always takes a photograph and puts a “research” slant on it that was not there. In this case, I had heard from folks in the McMurdo community, mostly helicopter pilots and not scientists, that they had often seen orcas on the ice edge. I heard more and more stories about orcas coming close to people when they landed near the ice edge. I therefore asked for permission to try to film these orcas for a film in 2001 that was produced by WNET/Thirteen for the Nature series that airs on PBS. We had great luck. I can tell you that it was our team and film crews after us that dove with the orcas, and I don’t believe any scientist has ever done so.

This bothers me, because it devalues professional photographers and the work that we do. Natural history photographers chronicle wildlife and natural history events and are sometimes are the first to do so. On occasion they are also the first to discover new behaviors or species. When the media uses our images to sell copies, the text often states that we were there documenting research. The implication is that witnessing and documenting the event, and the photographs themselves, is not good enough.

I am always appalled at how little the camera manufacturers respect professional photographers. Sure, they’ll use our images in their advertising calendars and in magazines sometimes. However, when you see an ad for Canon cameras on TV, you see tennis players in the ads. If you see a Nikon TV ad, you’ll see Ashton Kutcher touting the gear. What happened to the professional photographers who are actually getting out there, sometimes risking their lives, and using the gear? This is a pretty big slap in the face to photographers.

About the author:

Norbert Wu is an independent photographer and filmmaker who specializes in marine issues. His writing and photography have appeared in thousands of books, films, and magazines. He is the author and photographer of seventeen books on wildlife and photography and the originator and photographer for several children’s book series on the oceans. Exhibits of his work have been shown at the American Museum of Natural History, the California Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

He was awarded National Science Foundation (NSF) Artists and Writers Grants to document wildlife and research in Antarctica in 1997, 1999, and 2000. In 2000, he was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal of the United States of America “for his contributions to exploration and science in the U.S. Antarctic Program.” His films include a pioneering high-definition television (HDTV) program on Antarctic’s underwater world for Thirteen/WNET New York’s Nature series that airs on PBS.

He is one of only two photographers to have been awarded a Pew Marine Conservation Fellowship, the world’s most prestigious award in ocean conservation and outreach. He was named “Outstanding Photographer of the Year” for 2004 by the North American Nature Photographers Association (NANPA), the highest honor an American nature photographer can be given by his peers.