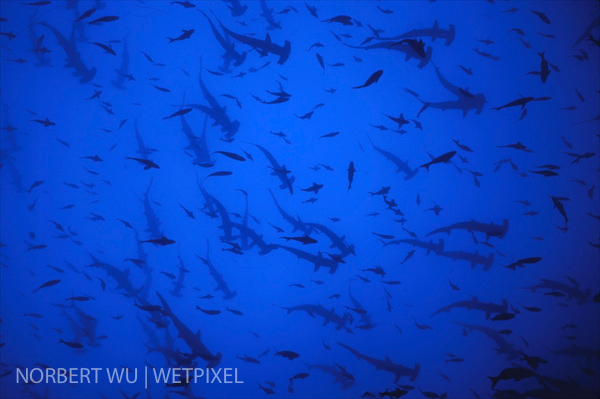

Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: School of Scalloped Hammerhead Sharks

Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: School of Scalloped Hammerhead Sharks, Cocos Island, Costa Rica

Thanks to all of you for your comments about my weekly series, where I show and talk about the stories behind some of my favorite images. I’ve been trying to start with images from my early days, and then progress chronologically.

I remember seeing the first images of these schools of scalloped hammerhead sharks from Cocos Island (taken by a friend and mentor, Marty Snyderman). Marty was one of the first underwater photographers to spend significant time at Cocos Island, and I saw his images back in the late 1980s as I was just starting to seriously take underwater photographs professionally. I was lucky enough to be able to go out with a couple of the diving vessels that visited this remote island. These images were taken on my first trip out there, aboard the Okeanos Aggressor. I later visited Cocos Island a few more times, all on the vessel Undersea Hunter. As far as I know, both vessels still visit Cocos Island, and despite all the hunting of sharks for their fins, these schools of hammerhead sharks can still be seen out there.

I had gotten tips from my friends (and bosses, when I worked on their films) Howard Hall and Bob Cranston. This was in the days before relatively inexpensive rebreathers were available. The trick, from what I gleaned, to getting images of these sharks was to get underneath them and to hold your breathe. The instant you let out your breathe, then the entire school of sharks would scatter. The school of sharks tended to swim around various underwater pinnacles near Cocos Island, hanging out around the thermocline, a pretty discrete boundary between warm, clear water and murkier, colder water. The sharks seemed to like this boundary. The boundary was generally right around 120 feet or so.

That first trip on the Okeanos Aggressor was something. A group of divers from Boston had chartered the boat, but I had been able to get myself and my friend Peter Brueggeman on the trip. Peter was a great friend and helpful to me underwater (and topside too!), and he had a great sense of humor and easygoing personality that helped offset my seriousness and antisocial behavior (I have really bad hearing, which contributes to my not enjoying conversations on dive boats – I have a hearing aide but don’t use it when I am on diving trips since it costs a lot when I forget I have it on and step into the water). The funny thing about that trip was how nearly everyone in the group from Boston ended up romantically involved with someone else in the group. There was a doctor who accidentally bumped into an old flame and rekindled the romance – but also spent the entire trip anguishing over what would happen when he got back home and his wife found out about the affair. There was a woman who targeted nearly every male on board and had a brief affair. Peter and I were left alone, which was fine with me as I was more concerned about getting images. I later discovered from one of the group that they thought that Peter and I were a gay couple! This was pretty surprising to me. It’s happened to me a few times since, because I like to travel with my friends, and two guys traveling together must mean that they are gay, I guess.

I can remember the dives on that trip well. Peter and I would go down a pinnacle called Dirty Rock, hang out at about 100 feet, looking off the pinnacle to catch a glimpse of sharks. I’d see them infrequently, just at the edge of visibility, circling the pinnacle. Once I caught a glimpse, I’d swim as fast as I could to the school, holding my breathe, and usually swimming upside down so I could see their silhouettes above me. If I was lucky enough to find myself underneath the school of sharks, I’d have just a fleeting few seconds to snap a couple of exposures (using a Nikonos V camera loaded with 35mm film) before I’d have to let out a breathe. The sharks would scatter at that point, and I’d look back the way I came to try to see the pinnacle. Most of the time I’d see Peter’s bright yellow fins, which were a lifesaver. Thanks, Pete.

Getting back to the pinnacle was important; I sure did not want to lose track of where I was and have to surface in the middle of the usually-turbulent, rainy ocean off Cocos Island. If I had not come back to where the other divers were, chances were good that the dive tenders would not see me when I surfaced, and I’d face a long time alone drifting. That kind of scenario – being lost by yourself, drifting away from your dive boat in stormy seas and low visibility – is so frightening to me now that I probably would not do this kind of dive this way any longer.

Sharks around the world have been targeted for years by fishermen who catch sharks only for their fins. It’s a tragedy. The fins are valued as a delicacy by the Chinese (yes, I am Chinese-American) who make the fins into shark-fin soup. Chinese folks try to serve shark-fin soup at wedding banquets, largely because it is very expensive, and serving your guests the most expensive dishes at a meal shows respect and courtesy. This tradition is actually a relatively recent phenomenon, which has arisen with the rise of the middle class in China.

The soup itself, and the cartilage from the shark fins, is pretty tasteless. The shark fin part of the soup tastes like rubber, with almost no taste. It’s a real tragedy that sharks are being targeted for this fishery. As apex predators, there just aren’t that many sharks out there (they reproduce and grow relatively slowly compared to other fish); and they are being wiped out for this ridiculous and young tradition.

Of all the issues in marine conservation today, I believe that convincing the Chinese people to stop serving and eating shark fin soup is perhaps the only issue that can possibly be resolved. I hope that we humans can stop this practice. I don’t think that we’re going to solve much else, like global warming or the problem of plastic debris.

About the author:

Norbert Wu is an independent photographer and filmmaker who specializes in marine issues. His writing and photography have appeared in thousands of books, films, and magazines. He is the author and photographer of seventeen books on wildlife and photography and the originator and photographer for several children’s book series on the oceans. Exhibits of his work have been shown at the American Museum of Natural History, the California Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

He was awarded National Science Foundation (NSF) Artists and Writers Grants to document wildlife and research in Antarctica in 1997, 1999, and 2000. In 2000, he was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal of the United States of America “for his contributions to exploration and science in the U.S. Antarctic Program.” His films include a pioneering high-definition television (HDTV) program on Antarctic’s underwater world for Thirteen/WNET New York’s Nature series that airs on PBS.

He is one of only two photographers to have been awarded a Pew Marine Conservation Fellowship, the world’s most prestigious award in ocean conservation and outreach. He was named “Outstanding Photographer of the Year” for 2004 by the North American Nature Photographers Association (NANPA), the highest honor an American nature photographer can be given by his peers.