Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: Shark Diving in San Diego

Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: Shark Diving in San Diego

I spent two years as a graduate student in Applied Ocean Sciences at the world-famous Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. This was approximately 1988. Macs were still in their infancy, but I had started with the original Mac in 1983 and used a Mac (SE?) while I was at Scripps. I used Word 5.1a, which did everything I needed it to and which I wish were still around. Lately I have been trying to find a way to convert all these Word 5.1a files, which I could convert to newer Word format files using Word X for the Mac. With Mac’s OS 10.7 and 10.8, which did away with the Rosetta emulator allowing Power-PC-based programs like MS Word X to work, I have lost the ability to open my old Word 5.1a files. I am seeking someone who can write me an Applescript to open all those old Word 5.1a files on my last Snow Leopard machine. Those files just need to be opened in Word X and then saved.

Back to the story. I was not a very good graduate student. The Applied Ocean Sciences program was for engineers interested in oceanography. I had graduated from Stanford with degrees in electrical and mechanical engineering, which is why the faculty at Scripps were interested in having me attend the school (and become their slave). But to be honest, I always knew that I was not that great an engineer. I was fine at software stuff, and I had even spent a year as a software analyst in Silicon Valley after getting my masters degree in mechanical engineering (computer science specialty) at Stanford. But I was just not that brilliant at doing stuff in the physical world, which is what Scripps oceanographers wanted. I had come to Scripps already a serious underwater photographer, and I had had a portfolio and photographs published in those old, now-deceased, but great publications Sea Frontiers and Underwater USA. Remember those magazines?

I had envisioned spending my time at Scripps by somehow combining my interest in underwater photography with oceanography. Unfortunately, the reality of being a graduate student is that you need to find an adviser to fund you. All advisors have their own specialties and interests and no one at Scripps was interested in what I wanted to do. My first advisor wanted me to work on a gravity meter. My second advisor was more interested in underwater optics than anything having to deal with marine natural history. And I was unfortunately completely and totally fascinated by marine life rather than the physics of water.

The field of marine biology is a tough one. (It’s not as fun as it used to be, and there is little money available.) One fellow student at Scripps finally received his doctorate, after eight years of hard work. His job prospects are dim; every job he has applied for has had a minimum of 70 applicants, and some as many as 200.

Nowadays, many marine biologists seem less concerned with natural history than their predecessors were. Scientists in the old days had many mysteries to solve. Where did eels go to spawn? Where did sea turtles spend the first two years of their life? What exactly were these strange life forms trawled up from the deep? Good science is no longer so simple. Most marine labs have turned to biochemistry and other laboratory-oriented research; research areas that can yield quick results and are good candidates for research funding. Field biologists are few and far between, and their financial situations are often dire.

In some ways, natural history photographers have taken over the role filled by old-time naturalists/scientists looking to represent and explain the big picture. While a modern research scientist may be forced to spend months and years studying a very small issue, I have the luxury of presenting my work without the burden of proof he or she must bear. The fact that I catch something on film makes it valid, and sometimes valuable.

I visited a man named Howard Hall, who lived in a suburb of San Diego. He had written a book called Successful Underwater Photography, which was my Bible back then. This was the first book that I had come across which explained how to take good underwater photographs with the equipment available those days. It was a deceptively simple, very clear book – and I am sure that dozens if not hundreds of underwater photographers got their start with that book. Howard was just starting to think about doing a one-hour film on California’s marine life; and he invited me to join him shark diving off the San Diego coast. I immediately accepted, and had a great time when the day came, getting my first glimpse of wild sharks, and having a 6-foot mako shark pass me by very closely. I was excited, thrilled.

The only problem was that the next day, I ran into my advisor at Scripps. I had missed a meeting with him on the day of the shark dive and had completely forgotten about it. When he asked why I had missed the meeting, I naively told him the truth; that I had gone shark diving instead. I innocently thought that he would be as thrilled as I was. Of course he wasn’t. That was pretty much the end of my time at Scripps.

I spent more time in San Diego, and I worked as an assistant diver on Howard Hall’s film Seasons on the Sea, which went on to win all kinds of awards. I spent many more days diving with the blue and mako sharks off the coast of San Diego. Marty Snyderman and Bob Cranston had a business bringing divers on these shark dives, and I was fortunate enough to be able to tag along on some of them and get in the water to shoot once in a while. (Thanks Marty and Bob! Marty: See, I am giving you credit for being the first San Diego shark diver guy. Bob, I know you don’t care about getting credit and just want to be in the water).

(Editor’s note: Sadly since Norbert wrote this article, Bob has passed away. I felt that Norbert’s comments are another poignant reminder of how Bob’s life impacted on some many people and have left them unedited.)

One of my first-ever assignments was for an advertising agency who wanted me to photograph a menacing shark near a diver.

After the shoot, I wrote an article for Photo District News. I probably have that article and the ad in the files somewhere and will post a scan here if and when I find it. Here’s the text to the article (which I found in my computer files as a Word 5.1a file – thanks Word X and Snow Leopard!).

Swimming with Sharks

Photographing Sharks for a Medical Advertisement

When Ellen Walton at the Frank J. Corbett agency called me, I thought that this would be just another standard stock sale. She had learned of my work in marine wildlife photography through word-of-mouth after scouring through the submissions of several stock agencies which specialized in natural history material. Walton, however, was looking for a very specific type of photograph, and none of the submissions from the agencies quite fit the bill. She mentioned that she had to paid hundreds of dollars in research fees without finding a shot that would work. This was not surprising to me, considering her description of the desired image. Her agency wanted to use a shot of a photographer with a menacing, large shark, to serve as the centerpiece of an advertising campaign for OptiRay, a medical solution used in cardiac imaging technology. The slogan for the campaign was “There’s Always a Safer Way to Get a Great Picture.”

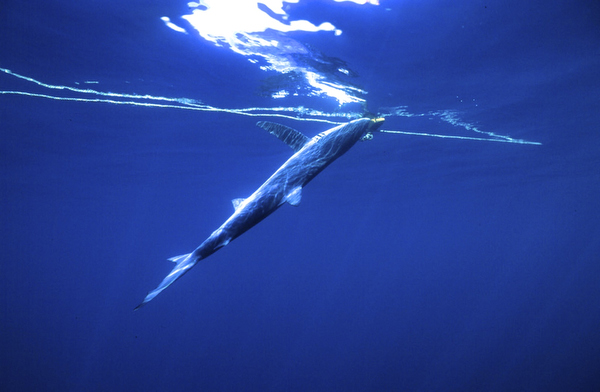

Ms. Walton requested stock images that might fit her criteria. I sent her a selection of my stock photographs of sharks and divers along with a note letting her know that I had the resources available to conduct a shoot specifically for this job. Living in San Diego, I had made the acquaintance of a group of divers who regularly took tourists out to see and photograph open-ocean blue sharks, a relatively common predator, and one of the few species which has been documented to attack man. Blue sharks are fairly predictable animals, and although they are certainly dangerous, they don’t get quite large enough to crush a man in their jaws, and their teeth, although razor sharp, are short and stubby. In contrast, a mako shark has long, slender teeth. Mako sharks are not as common as blue sharks, and they are much harder to photograph than blue sharks. The difference in their teeth structure is crucial. Jeremiah Sullivan, a diver and photographer in San Diego, developed a working shark suit in the 1970’s, specifically to protect against attacks by blue sharks. Only four or five of these suits were ever made, with a cost of $6000 each. The suits are made of stainless steel links woven together electronically into a tight mesh. The mesh covers the diver’s entire body and allows enough flexiblity to swim and move around in. The stainless steel mesh works by spreading the point of impact of a shark’s tooth into a more generalized area. I’ve been bitten several times since first trying on the suit, and it really works! Even a large eight-foot shark can bite my arm with no blood or bruises afterward. A mako shark’s teeth, in contrast with the blue shark’s, would probably tear right through the steel mesh. No one has ever been attacked by a mako shark while wearing one of these suits, and this is where good judgment and experience in filming large animals comes into play.

The real danger of photographing sharks in this steel suit comes with its weight and restrictiveness. To find blue sharks, Bob Cranston, the captain of the boat that leads these popular excursions, pilots his boat twenty miles out into the open ocean. The bottom here is over two miles down, and a novice diver might easily become disoriented by the endless, bottomless, three-dimensional blue space all around him. Diving in the open ocean can be disorienting due to the three-dimensionality of the water. It is easy to go down very deep, very fast, without realizing it until it is too late. There are no visual clues to indicate where or how fast a diver might be sinking. The neoprene of a wetsuit compresses at depth, making a diver even heavier relative to the water around him, and so the deeper a diver sinks, the faster he may go. This is an exceedingly dangerous situation. Only experienced divers attempt blue-water diving in the open ocean. When Bob Cranston leads groups of tourist divers out on his trips, he always personally escorts them from the boat to the shark cage during a practice dive and during the actual shark dives to make sure that his clients do not fall victim to this disorientation. Add the weight and relative inflexibility of a shark suit to the inherent problems of blue-water diving, and small problems can quickly become dangerous situations. Divers use a piece of equipment to adjust their buoyancy in the water, which effectively acts as a parachute to keep them from sinking down too fast. This is called a buoyancy compensating device (BCD), and it is an adjustable volume air bag into which air is pumped to keep the diver neutrally buoyant. The shark suit itself weighs a good 20 pounds. However, the BCD is easily punctured by frenzied sharks, and a diver could easily find himself sinking out of control, down to the bottom two miles down, with a twenty pound, $6000 stainless steel anchor, impossible to take off underwater. This is the danger, and it is not a glorious prospect. We shark divers have learned to pay constant attention to our surroundings, our depth, and the location of our buddies. Ironically, as with most things in the ocean, it is not the sharks, but rather a diver’s carelessness that leads to dangerous situations.

Ellen Walton sent me a layout showing the type of image that she wanted for the ad. The shark was very large and menacing in the frame, with a mouth full of big, serrated teeth, and a photographer in a shark cage, very small in the frame. The shark looked much like the great white shark from Jaws, one of the most fearsome and awe-inspiring predators in the world. Unfortunately, white sharks are simply not found easily. Avid divers regularly pay $10,000 and upwards for the chance to see one of these animals. The money goes toward a week on a boat along with vast amounts of chum consisting of horsemeat, tuna, and assorted guts and blood of other animals. With all this expense, there is still no guarantee of seeing a great white shark. I would not be able to provide the great white shark for Frank J. Corbett for the day rate that we had agreed upon. One of the reasons I had landed the job was that my estimation of day rate, boat rental, shark cage and shark suit rental, bait, and other expenses was less than what the agency would have had to pay to combine two photographs of a shark and photographer in a Scitex computer . I made all of this clear to Ms. Walton before proceeding. Bob Cranston had his method for attracting blue sharks down cold; by hiring his boat, I was virtually guaranteed to be able to photograph blue sharks close enough to get the composition that I wanted. The biggest problem was that blue sharks hide their teeth until they feed! Like the creatures from the movie Alien, blue sharks have jaws that actually protrude out when the shark is biting. Until the moment of impact, however, the teeth and jaws are recessed. To get the composition that Frank J. Corbett wanted, I would have to be within inches of the shark.

The actual taking of the photograph was simple compared to the vast amount of work involved in getting to the open ocean site twenty miles offshore, unloading the shark cage, putting out a sea anchor (which keeps the boat from drifting away while you are chasing a shark around), and chumming the water with bait to attract the sharks. Bob Cranston, as my model and chief shark handler, was in charge of baiting the sharks into range and keeping an eye on my back. Another diver was in the shark cage, serving as a model and keeping an eye on Bob and me. Yet another person stayed on the boat at all times to keep watch for changing weather, keep the chum line going, fill tanks, and help us out of our suits.

For equipment, I chose a Nikonos V amphibious camera with an Ikelite Substrobe 150 flash. The Substrobe 150 is a large, powerful strobe with a very wide angle of coverage, more than enough to cover the 15mm wide-angle lens that I chose. To make the shark appear as large and threatening as possible, I knew that the shark’s face needed to be as close to the lens as possible. The 15mm Nikonos lens is an exceedingly sharp lens specifically designed for use underwater. To make the shark appear large in relation to the diver, I tried to shoot only when Bob was a few feet behind the shark. The Nikonos is a 35mm camera system, and so I stayed with very fine-grain films, using both Fujichrome 50 and Kodachrome 64. Kodachrome 64 is my preferred film in such situations. Its high contrast works well in the diffuse light underwater, rendering subjects sharp and crisp. Fujichrome 50 is a better choice in greenish water, as color balance makes greenish water appear bluer and more appealing. The agency had planned to use the photograph in a number of sizes, one blown up to poster size for a tradeshow, and one as a full-page size ad in a number of medical magazines.

Although we were shooting in sunny California, light underwater is always at least two stops below light levels on the surface. Twenty miles offshore in the summer, fog usually prevails, and the day of the shoot was no exception. Light levels underwater were low, and so the higher speed of Kodachrome 64 was a help. To show the shark and diver in a background of blue water, it was necessary to use strobe light as fill, adjusting the strobe output to match or just barely fill in the colors and details of the subjects, while relying on ambient light to provide primary exposure. To provide the agency with a variety of lighting situations to choose from, I varied my strobe fills and primary exposures over a wide range of exposures. Over the course of the day, I shot about 300 exposures, or 8 rolls of film. Each roll of film was exhausting and time-consuming. To change film, I had to swim back to the boat, haul myself and 100 pounds of gear onto the boat, rinse the camera and strobe off with fresh water, and change the film. While shooting, Bob and I would swim with a shark, attempt to photogrpah a large, fast-moving shark in a natural position, with Bob attempting to both attract the shark to us, point it toward my direction, and then hold a pose as a photographer. After shooting a few exposures, we would both have to swim back over to the shark cage, which had been dragged by the wind and boat for twenty to thirty yards. Swimming in the shark suits while carrying large and bulky photographic gear was exhausting, and so we would have to hang onto the cage for a few minutes to rest and catch our breath. Working hard underwater causes you to breathe hard and forcefully, and many divers are familiar with how difficult it is to get enough oxygen into our lungs to feel rested again. Our air tanks were thus rapidly depleted, and changing tanks took yet another difficult swim back to the boat and a change of gear.

Ellen Walton wanted to see the film immediately, and so the Fujichrome film was processed the and shipped via overnight courier the next day. The Kodachrome took a day longer, and the agency ended up using a dark, moody shot of a diver and shark. Out of those 300 exposures, only one or two shots fit the bill exactly, so I felt lucky. But what is luck? I believe that you make your own luck, by shooting different compositions, exposures, and hedging your bets.

Reading this article brings me back to those old days. I was just starting out as an underwater photographer, and I had a pretty high opinion of my photographic abilities back then. It seems that all budding serious underwater photographers think that they are the bomb if they bring back a few decent images. I have lost track of how many egotistical young divers have approached me armed with some underwater images that they call “abstract”. By taking these “abstract” images, they consider themselves “artists.”

I have my own view. I think that you are a technician, someone who might be able to take technically decent images that are in focus and have the correct exposure, as a serious beginner. Some folks never get past being good technicians. You see their photos all the time, they love their own work, but it is missing that spark; it’s usually a straightforward documentation of an animal. Photographers who become serious will move beyond the technician stage, and by shooting more and more (and these days, shooting thousands of images on one subject) will usually get a few images that have that “spark” and which are special. I’d venture to say that few photographers become true artists. The artists are the experts who have mastered the technique so that it is second nature and know their subject matter so well that their best images blow your socks off. They know their subjects, the environment, and their gear, and are able to produce mind-blowing images that say something about their subject or that moment in time.

Back to the story! This was written in 1988 or so. Those were the days of the Nikonos V camera, 36 shots per roll of film, plenty of sharks off San Diego, Kodachrome 64 film, “rush processing of film”. Some things never change. As far as I can tell, BCs haven’t really changed in 30 years.

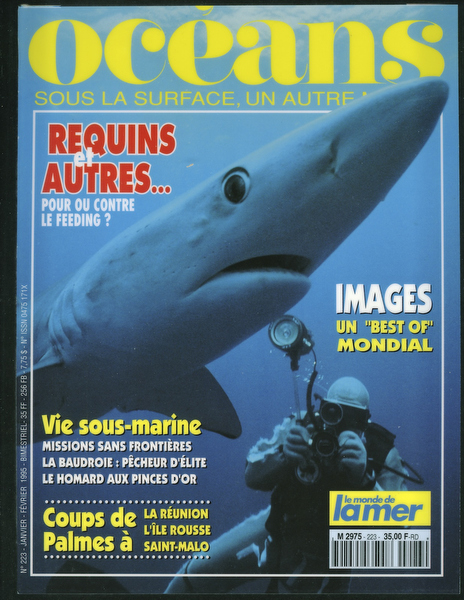

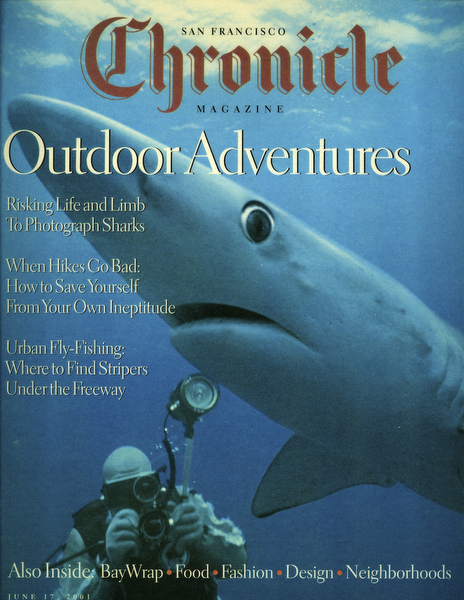

The image from that shoot was published a bunch of times. Here are a couple of covers.

About the author:

Norbert Wu is an independent photographer and filmmaker who specializes in marine issues. His writing and photography have appeared in thousands of books, films, and magazines. He is the author and photographer of seventeen books on wildlife and photography and the originator and photographer for several children’s book series on the oceans. Exhibits of his work have been shown at the American Museum of Natural History, the California Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

He was awarded National Science Foundation (NSF) Artists and Writers Grants to document wildlife and research in Antarctica in 1997, 1999, and 2000. In 2000, he was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal of the United States of America “for his contributions to exploration and science in the U.S. Antarctic Program.” His films include a pioneering high-definition television (HDTV) program on Antarctic’s underwater world for Thirteen/WNET New York’s Nature series that airs on PBS.

He is one of only two photographers to have been awarded a Pew Marine Conservation Fellowship, the world’s most prestigious award in ocean conservation and outreach. He was named “Outstanding Photographer of the Year” for 2004 by the North American Nature Photographers Association (NANPA), the highest honor an American nature photographer can be given by his peers.