Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: Spotted Dolphins, Bahama Banks

Norbert Wu’s Favorite Images: Spotted Dolphins, Bahama Banks

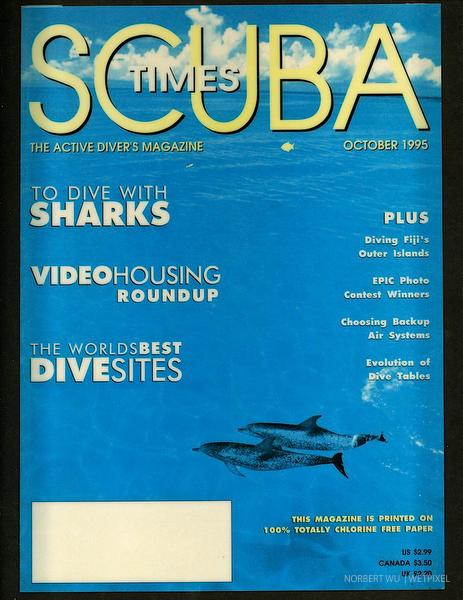

This is one of my favorite images, of all my favorites. Seeing this image brings back memories of a hot, humid summer day at sea, the sea glassy with the shallow sand banks spread out before me, while I stood on the bow of the boat the “Dream Too” watching a pod of dolphins swim by languidly. Thanks to Captain Scott, Robin, and Inez Wagner for helping me get to this place several times in the 1990s.

A group of wild Atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis) have interacted with humans in their home range for over twenty years, after their initial discovery by treasure hunters. They will often approach swimmers in the water, and they seem to enjoy swimmers that try to match their speed and movements. These Atlantic spotted dolphins rest on shallow sand banks during the day, after a night of hunting in deep water.

A pair of Atlantic spotted dolphins rest on shallow sand banks during the day, after a night of hunting in deep water. Bahama Banks.

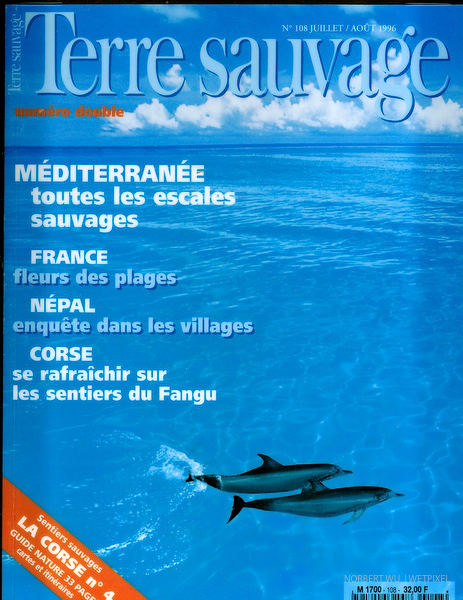

This image had plenty of “negative space” for magazines to use for text, so several magazines used this image on their covers.

The French, being French, liked this image, but of course they had to mess with it. They flipped the image which was fine with me. But then they removed all the spots on the dolphins’ bodies. This was ridiculous; it was like removing spots from a leopard to make it look better.

Here’s some text that I wrote about these dolphins several years ago:

A Special Place

There are a few very special places in the world, places where man can interact with wild animals who come to him of their own accord. One of these magical places is the shallow sand bank that extends to the north of Grand Bahama Island. Here, the famous spotted dolphins of the Bahamas come to humans to play, to interact. This is the only place in all the world where wild dolphins regularly come of their own free will to interact and play with humans. These wild dolphins have not been fed or otherwise lured. They are apparently drawn to humans for the sheer enjoyment of this inter-species play. They were first discovered by treasure hunters searching for sunken Spanish galleons. The men would take time off from their labors and play with their new friends. Since then, these dolphins have been swimming with people for almost twenty years, three dolphin generations! A few scientists and boat operators, such as Captain Wayne Scott Smith of the “Dream Too”, have even kept track of calves from the time they were born to the time they gave birth to their own calves. Captain Scotty is a virtual dolphin himself. He is a self-trained naturalist and has devoted his life to studying and interacting with these dolphins, and he has identified some 200 individuals.

The dolphins rest during the day in a 20-foot-deep sand bank north of Grand Bahama Island. The white, reflective bottom and shallow, clear water (with visibility frequently over 100 feet) make conditions often ideal for photography. However, it can also be turbid, rough, dark, and/or rainy. There are several boats that take passengers out to see these dolphins.

These trips have been acclaimed by all who go as a rare privilege to swim with these beautiful animals, observe behaviors such as mating and feeding, and to come away with some fantastic photographs. Swimming with these dolphins is exhilarating, refreshing in every sense of the word. Since the dolphins love to play, the best way to hold their interest is to snorkel with them, twisting and turning, interacting with them at their level. They will often approach swimmers closely, mimicking their actions. Although the dolphins off Grand Bahama love to swim with humans, they don’t like to be touched. They will swim closely until you put a hand out. Mimicking a fin by extending an elbow is fine. Sometimes the dolphins are not in the mood to accept a human intruder. If you swim into their midst, they will move off and give you a clear signal of displeasure by expelling excrement.

There are 60 to 100 individuals in the Bahamas Banks population, but we usually see only four to twelve at a time. These dolphins do most of their hunting at night, when they pursue squid in the deep waters off the bank. They rest during the day in a shallow, warm, and clear sand bank. These dolphins are the only known successful predator of the elusive razorfish, which dive headfirst into the sand to escape danger. Dolphins, unlike other predators, use their sophisticated sonar capabilities and high intelligence to track the razorfish, then dig up and capture them with a quick snap of their beaks.

By spending time with these animals, I’ve seen activities such as mating, playing, aggression, and nursing. Dolphins are quite passionate animals, and they spend almost as much time engaged in sex and foreplay as humans do. When mating, the male swims upside down, directly under the female. Up to six other males, called “helpers,” will swim with the couple, supporting them and warning off intruders. It is an interesting spectacle. I’ve been struck by how the helpers will swim at me, in an attempt to keep me away from the mating pair. Most of the footage of wild dolphins shown on television is of this group.

Spotted dolphins love to play underwater. I have seen them grab objects and pass them to and from each other at high speeds, and they will often leave that object in the water, seemingly waiting for you to join in the game. Like many species of dolphins, they will often come up to the front of our boat and ride the pressure wave, similar to bodysurfing. Many scientists have written papers and spent hours observing this phenomenon, only to come to the conclusion that there is no logical reason for this dolphin behavior. It’s pretty obvious to all but the most detached observers that dolphins ride waves for fun.

Dolphins have always held a special fascination for humans. Stories of their intelligence, their altruism, and their physical abilities abound as myths of the sea. Carlos Eyles summarizes the human fascination with these animals: “The dolphin embodies all that humans have discarded; all that humans have lost. They live in large families, they play, they make love, they operate out of truth. Their sonar can “read” an entire biophysical system in a micro-second. When the truth is not spoken that system changes, thus they can immediately distinguish a lie from the truth. But of course the don’t have to. Their society works. It has stood the test of time for thirty million years.“

On my last dive with the dolphins this past fall, a cold front of water from the north had brought rarely-seen visitors to the banks. Schools of bonito (a type of tuna) and large sharks cruised through waters that had misted up from the sand, like clouds. A large bull shark appeared out of the mist and approached me. Knowing that this is one of the more aggressive and dangerous of all sharks, I was stuck by a surge of adrenaline as the shark approached me closer and closer. In the meantime, the dolphins played around at the surface, hanging in the area for an unusually long time. I fired off my final frame, made a sudden movement, and the shark turned and sped off into the distance. The last photograph on that roll shows the shark turning away, with the dolphins cavorting in the distance, playing in the last rays of the sun. I cannot help but wonder, each time that I look at that photograph, if the dolphins were watching over me, waiting until they were sure that the dangerous shark had passed. Or maybe it was something else, as one scientist put it: “There are plenty of stories about dolphins pushing drowning humans in to shore to save them. But you never hear from the humans who were pushed out to sea.”

About the author:

Norbert Wu is an independent photographer and filmmaker who specializes in marine issues. His writing and photography have appeared in thousands of books, films, and magazines. He is the author and photographer of seventeen books on wildlife and photography and the originator and photographer for several children’s book series on the oceans. Exhibits of his work have been shown at the American Museum of Natural History, the California Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

He was awarded National Science Foundation (NSF) Artists and Writers Grants to document wildlife and research in Antarctica in 1997, 1999, and 2000. In 2000, he was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal of the United States of America “for his contributions to exploration and science in the U.S. Antarctic Program.” His films include a pioneering high-definition television (HDTV) program on Antarctic’s underwater world for Thirteen/WNET New York’s Nature series that airs on PBS.

He is one of only two photographers to have been awarded a Pew Marine Conservation Fellowship, the world’s most prestigious award in ocean conservation and outreach. He was named “Outstanding Photographer of the Year” for 2004 by the North American Nature Photographers Association (NANPA), the highest honor an American nature photographer can be given by his peers.