Peter Scoones: 1937 - 2014

A tribute to Peter Scoones by BSoUP co-founder Colin Doeg.

Peter Scoones, one of the world’s legendary wildlife underwater cameramen, has died after a defiant battle against cancer. He was 76.

Co-founder of the British Society of Underwater Photographers (BSoUP), he learned photography while serving in the RAF in Singapore in 1959. He was so captivated by the colourful tropical fish he saw while snorkelling to clean the hull of his sailing dinghy that his passion switched immediately from boats to recording the life and scenery he saw in the warm tropical water. Unofficially, Royal Navy divers trained him to dive using oxygen rebreather equipment but subsequently he changed to air and housed his first cameras in boxes made from bits of Perspex from aircraft windows.

Returning to civilian life, he became increasingly involved in the development of equipment for the off-shore oil industry. However, by 1979 underwater photography took over as his main commercial activity. He became involved in the filming of TV commercials and features, but his heart was always in the natural history and documentary fields. His break came when the BBC Natural History Unit mounted an expedition to the Comoros Islands to search for coelacanths, a fish once thought to have been extinct for millions of years. Word had reached the Unit of a special low-light camera that Peter had developed. They wanted to hire it but he said it was only available if he could come along to operate it. That was the first time he met Sir David Attenborough, the familiar face and voice of so many natural history films and documentaries.

In those early days the only way to film in the depths of the Mozambique Channel was to suspend the camera from a 320m-long cable but after many unsuccessful days of searching it jammed in the cleft of a reef and was lost.However, as the crew were packing up to return home, Peter learned a fisherman had caught a specimen and it was tied to his canoe in the local harbour. He persuaded the fisherman to let him photograph the fish. It made a few swimming movements while Peter filmed it and took still pictures. They were the first in the world of a living coelacanth.

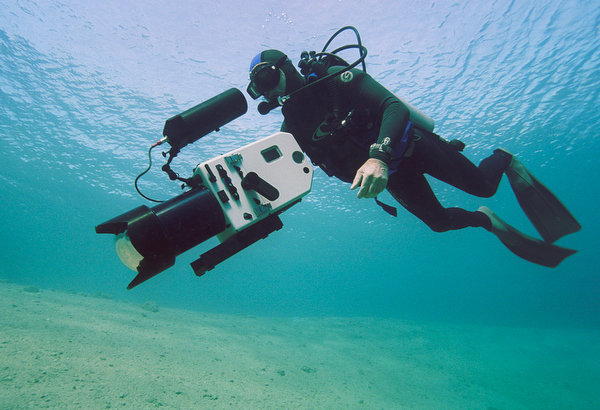

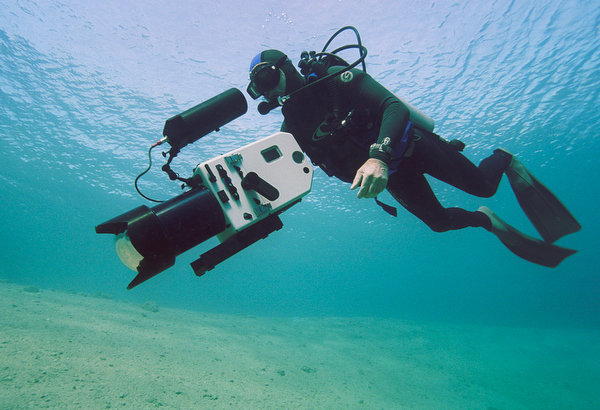

Scoones went on to become one of the Unit’s core underwater cameramen. He played a major part in many ground-breaking series including the first live outside broadcasts from underwater in the Red Sea. Peter was renowned for his self-sufficiency and resourcefulness in the field. Martha Holmes, one of the original bubble-helmeted presenters in that series who went on to be the producer on many of Scoones’ expeditions remarked: “Peter’s contribution to the underwater wildlife making community is immeasurable. He was a visionary who, ahead of the game, recognised that the advent of video cameras would revolutionise underwater filming. Others were slow to adapt, but Peter forged ahead modifying cameras to fit into his own underwater housings. Not only would he do this in the comfort of his workshop, he would be doing it on a rolling boat in the middle of the Southern Ocean, or minutes before an annual marine event that would not wait for him or his perfections.”

“For 30 years Peter was at the forefront of underwater filming technology. For Reefwatch, the first live broadcast from underwater, he advised on the adaptation of studio cameras for the equivalent of an underwater studio in the Red Sea. He led the way with his technical expertise and kept the cameras alive and well throughout Sea Trek, Life in the Freezer and Blue Planet. Peter always saw a problem as a challenge to be overcome, and overcome them he did.”

This ability enabled him to make special items to obtain unique footage such as operating a housed camera on a pole from the surface - the “pole-cam” is now widely used - to obtain the first shots of a great white shark swimming naturally in the sea rather than gnawing at the bars of a safety cage or at hunks of meat suspended over the side of a boat.

Talking about his talents, Sir David said that Peter had a remarkable gift for composition and understood fish as other cameramen understood chimpanzees or spiders. “He knew fish so well he could sense what they were going to do. You could see it in his footage. He moved as the fish moved.”

The late Rob Palmer, a noted cave diver, used to relish recounting how Peter ran out of air while far into the labyrinth depths of Jamaica’s Blue Holes. Calmly Peter spat out one mouthpiece, fished about with one hand, found that for his reserve air supply and switched it on. When viewed later the slow pan from one side of the vast chamber to the other was rock steady.

In 1999, for his significant contributions to underwater photography he was included in Scuba Schools International’s directory of the “world’s most elite divers” by becoming a Platinum Pro 5000 diver, joining the ranks of such pioneers as Hans Hass, Jacques Cousteau and many others. Said Joss Woolf, BSoUP’s chairman: “Peter was a legend in his own lifetime. As well as a pioneer and innovator, he was a perfectionist who always wanted to improve his footage. He was an inspiration to underwater photographers throughout the world.”

Said the Society’s co-founder Colin Doeg: “He was a driving force in the creation and progress of BSoUP, which was formed in 1967 and continues to thrive. He originated or was involved in the development of many features of underwater camera housings that today are commonplace and available off the shelf. “At first we used to meet in the front room of his house. He knocked down a wall so we had more space and could project our underwater images at a larger size.

“Even in the world of early underwater photographers he was unique. He was a fearless cameraman, taking everything in his stride from piranhas and killer whales to alligators and elephants as well as from diving under ice and deep underground but his trademark footage was shot on coral reefs. He always refused to eat reef fish, they were his subjects.”

Typical of the regard in which he was held by other underwater photographers and cameramen were the reflections of Wetpixel Associate Editor Alex Mustard. He said: “Peter was an innovator, never content merely to produce excellent images. He always wanted to push back the boundaries and thrill his audiences with visuals they had never seen before. His engineering prowess was instrumental in driving his creativity. His other trump card was his field craft. He knew where to find his subjects and how to approach them photographically.”

Over the years Scoones won many awards for his pictures and films. He won an Emmy and a Bafta for technical achievement for his work on both Great White Shark and Reefwatch. In addition, he was twice awarded a Palme d’Or at the Antibes Film Festival in France for his work. In 1993 he was named Diver of the Year by the British Sub-Aqua Club for his significant contribution to the diving industry. He was twice British Underwater Photographer of the Year and recently BSoUP, the Society he co- founded, awarded him its first lifetime achievement award for his exceptional contribution to underwater photography.

Unlike other cameramen, he did not attach lights to his cameras. Instead, the lighting was handled by his wife Georgette Douwma, herself a talented underwater photographer and artist. His buddy for a major part of his career, both underwater and in life, she instinctively knew how he wanted his subjects to be lit.

As well as Georgette he leaves two children by his first marriage, Fiona and Robin. Our thoughts go out to them at this terrible time.

There is a tribute page to Peter on Facebook if you wish to leave comments or personal tributes, or they can be posted here.