Rebreathers for Underwater Image Making by Nicolas Remy

Advantages of rebreathers for photography

It is no secret that rebreathers have key benefits for underwater image makers, yet, they are also more complex to dive and maintain than traditional SCUBA gear. Underwater photography is a gear-intensive pursuit by itself, combining both isn’t a straightforward decision. Having spent 800+ hours taking photos while on a rebreather (and 250 photo-dives without one beforehand), I certainly see several pros & cons to consider, before you invest $ 1000s on training and equipment. In this first article, I am going to cover the positives, and a second Wetpixel article will investigate the negatives. Using examples from my own experience, I will hopefully help you decide whether getting a rebreather is right for your own photographic journey.

Getting closer to wildlife

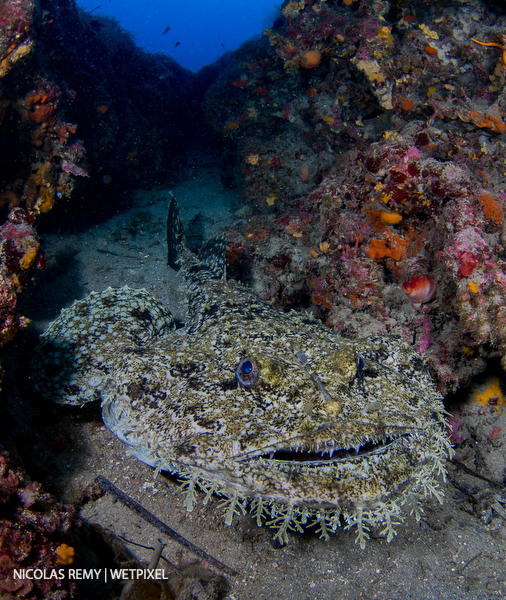

Perhaps the most sought-after advantage of rebreathers is getting closer to wildlife. With no bubbles and no first stage regulator noise, welcome to true silent world! Most marine critters will welcome the change too, allowing you to get closer. That change will be more or less dramatic depending on where you dive, whether spearfishing is allowed locally, and how often divers are visiting. My wife Lena and myself dove “le Graillon”, a popular shore-dive in the French Riviera for 4 years without ever seeing the endangered dusky grouper in that spot. The first time we ventured there with rebreathers, we saw three at the beginning of the dive! Moments later, we heard regulators in a distance, and the groupers we had insight into immediately went to hide. Even in places where fish are more comfortable with divers, such as Sydney’s shore dive sites, my rebreather gets me a tad closer to subjects. As we all know, getting just 50cm closer makes a big difference in underwater photography.

No bubbles ruining the show

Rebreathers are also beneficial when you need to get below marine life and/or frame upwards wide-angle compositions: no need to hold your breath to keep those distracting bubbles out of the shot or to avoid spooking the subject. Think about all the shots that you could have done better if you were able to hold your breath a tad longer. When diving Manta Bommie (Stradbroke Island, Australia) last year, I didn’t have to hold my breath while manta rays slowly cruised towards and above me. At some point, my wife was shouting in her loop to get my attention, as I hadn’t noticed the manta stationed just above my head.

Being more stable

Stability is essential for underwater photography and it is easier to get perfectly still on a rebreather than with traditional scuba gear: the breathing gas circulates between the unit’s counter-lungs and your own lungs, without any gas loss (for closed-circuit rebreathers), meaning without buoyancy changes. Think macro shots where you cannot lay down on the seafloor due to fragile marine life or a silty bottom, this extra stability can turn around the photographic productivity of a dive. Now, an experienced open-circuit diver can have great buoyancy control, timing their breathing pace to minimize any changes of depth. I would argue that it gets harder with distracted by photography, and impossible when the inevitable “hold your breath” scenario comes in (see the previous paragraph).

Staying down as long as you need

How often did you curse your SPG when a shortage of gas meant you had to ascend and abandon a great photo opportunity, such as a rare behavior? Rebreathers are game-changers on bottom time, with closed-circuit rebreathers (CCR) being best in this aspect: mine gets me 3 hours of no-decompression diving at 20 meters depth. For deeper or longer dives, decompression does accumulate, but slower than traditional scuba, as you’re constantly breathing an optimized gas mix, whatever the depth. Nowadays, my standard shore-dive (and most of my boat dives with open-minded operators) is 2h30 to 3h long.

More flexibility to plan your dive

This extra time opens lots of possibilities underwater: covering long distances, exploring further, navigating back & forth even against currents (within reason). There is just more flexibility in planning a dive. For example, one of the dive sites we enjoy at Bass Point (Australia’s south-eastern coast) features a photogenic underwater arch at 23 meters, but its shore accessibility is very dependent on weather, and dive boats seldom travel there. Our rebreathers allow us to start the dive in the sheltered Bushrangers Bay and travel underwater for around 600 meters until we reach that Arch and surrounding scenery. Taking our time to stop at every photo opportunity, the whole round trip makes a pleasant 3 hours dive, especially when humpback whales accompany our journey with their songs. Another day, we went boat diving along the northern limestone cliffs of Jervis Bay (Australia), with the standard plan being two dives at different spots along the cliffs, swapping tanks during the surface interval. Given our rebreathers, the skipper allowed us to stay down for a 2h30 dive, where we could follow the sand line and appreciate the dramatic underwater scenery, stopping wherever we saw photographic opportunities, for as short or as long as we wanted.

More flexibility to amend the plan

There is also flexibility to amend the dive plan, depending on which photographic opportunities appear underwater. Once diving Australia’s famous Fishrock, I spotted a large shadow in the distant blue, opposite direction from the mooring I was heading back to. Could it be the elusive school of hammerheads that sometimes visits the rock? Fair enough, I had spent a long time at depth already, reaching 10 minutes of mandatory safety stop, but my dive computer calculated that another 5 minutes at that depth would only increase my safety stop by 1 extra minute… Yes, I would be fighting a bit of a current on the way back, but hey, after 2 hours of diving I had only consumed 50 bars on my 3 liters oxygen tank, so there was ample gas available, including sufficient bail-out gas in case of equipment failure…

When you need your own space

Sometimes, the photographer’s challenge isn’t getting closer to marine life… but away from fellow homo sapiens! A few years ago, we dove the famous Umbria wreck on a Sudan liveaboard. The wreck has lots of photogenic features, including three WW2 Fiat trucks in one of its holds. However, some of its holds are silty, making it difficult to take clean photos when our dive buddies were swimming around. Given our ample gas supplies, and the friendliness of our dive operator, we had all the time needed to wait for fellow divers to visit, move out, let the silt settle down, and then start shooting, including having fun with remote strobes.

Communication across photographers and models

Communication between photo buddies can get frustrating, given the complexity of instructions to convey and rebreathers can help in these regards. It took us a while to get used to “speaking” in a breathing loop, and even if we’re not really formulating complex words nor sentences, we can understand simple sounds that convey meaning. Just being able easily to get each other attention is already a blessing: I just call my wife’s name and, provided there aren’t open circuit divers or engine noises nearby, she will notice me, flash her torch if we aren’t in sight, or just look at me for any modeling instruction. When Lena is hand-holding a snoot to help me with backlighting, and we’re trying to perfect the light beam angle, I will make appreciative sounds to let her know when the lighting is right. This way, I can give her feedback without additional hand gestures, hence avoiding compromising my own position or spooking the subject.

Conclusion

All-in-one, a rebreather allows you to maximize photographic opportunities, within the limits of your experience, equipment, and surface commitments. All isn’t green though, there are a couple of drawbacks to be aware of before you take the plunge, which I will cover in another article soon.

About the author

Nicolas REMY and Lena REMY are two awarded underwater photographers based in Sydney, Australia. Their work has been published in international media, where Nicolas writes about diving destinations, photographic equipment reviews, and marine life behaviors. Nicolas teaches underwater photography in the form of group classes, workshops, and private on-demand coaching.

Visit their website to see more of their work or to get in touch.