Study records humpback feeding behavior

WWF-Australia reports that Australian and US scientists working off the Antarctic Peninsula in the Gerlache Strait have managed to attach non-invasive camera tags with 3D motion sensors onto humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). The devices were stuck on their backs for 24 to 48 hours and recorded feeding behavior, including the animals lunge-feeding into tight swarms of krill.

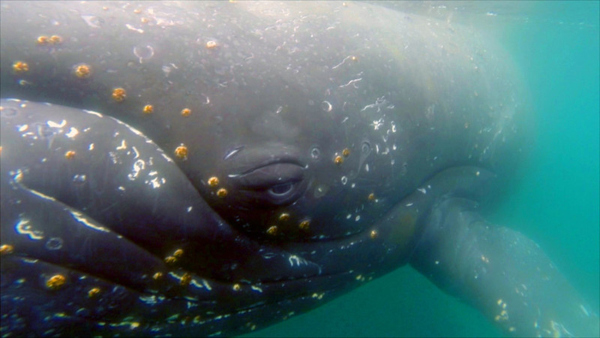

Scientists have attached cameras to whales to unlock the mysteries of their life in Antarctica … and it is revealing a bonanza of information.This includes where, when and how they feed, their social lives, and even how they must blow hard to clear sea ice so they can breathe.

Crucially, data being gathered will enable better protection of whale feeding areas. The researchers use suction cups to attach non-invasive digital tags — which contain sensors and a ‘whale cam’ — onto the backs of humpback and minke whales.As the whales plunge, we go below the surface with them and experience a day in the life of an ocean giant, including the various ways they feed on krill.

Dr Ari Friedlaender, an associate professor from Oregon State University and lead scientist on the whale study said,

“We have some wonderful data on different feeding strategies from rolling lunges near the surface, to bubble net feeding, to deep foraging dives lunging through dense patches of krill. We have been able to show that whales spend a great deal of time during the days socializing and resting and then feeding largely throughout the evening and night time. Whales are aggregating in a number of bays – including Wilhelmina Bay, Cierva Cove, Fournier Bay, Errera Channel – in high numbers and are feeding there for weeks at a time.”

“Every time we deploy a tag or collect a sample, we learn something new about whales in the Antarctic. Once we have an idea about where the whales feed, how often, where they go and rest, we can use this to inform policy and management to protect these whales and their ecosystem. They were gentle and curious and seemed as interested in us as we were of them. It is hard to describe the feeling of having a 15-metre, 40-tonne whale inches away from you, peering back at you. We were all extremely moved by this experience.”

The camera tags are on each whale for between 24 and 48 hours before they detach and are retrieved by scientists and reused. WWF provided funding for three of the ‘whale cams’.

Rod Downie, Polar Program Manager at WWF said:

“This technology and exciting science will help us to better understand the important feeding areas of whales along the Antarctic peninsula, and the impact of declining sea ice caused by warming temperatures.”

“The data will contribute towards the development of a network of Marine Protected Areas, conserving critical habitat not only for future generations of Antarctica’s ocean giants, but also for penguins, krill and thousands of other marine species. “

The research is being conducted in collaboration with scientists at the Australian Antarctic Division in Hobart and under the auspices of the International Whaling Commission’s, Southern Ocean Research Partnership (IWC-SORP).

The aim of the Partnership is to implement and promote non-lethal whale research techniques to maximize conservation outcomes for Southern Ocean whales.