The Big 4 by Mike Bartick

Cephalopods are the most intelligent invertebrate animal on the planet. They occur in almost every ocean worldwide ranging from temperate to tropical waters. They have been a food source for humans for centuries and of course, are a great source of protein for fish and other marine animals since day one. They are highly motivated for survival and have evolved with every challenge our planet has thrown at them, yet they endure. They are not just surviving but are thriving. Given the way they learn, I think it’s also safe to say that octopuses also seems wise.

For the Indo-Pacific region, the list of possible cephalopod encounters is almost limitless. Octopuses of many varieties, squid and cuttlefish, can be seen anytime and on nearly every dive.

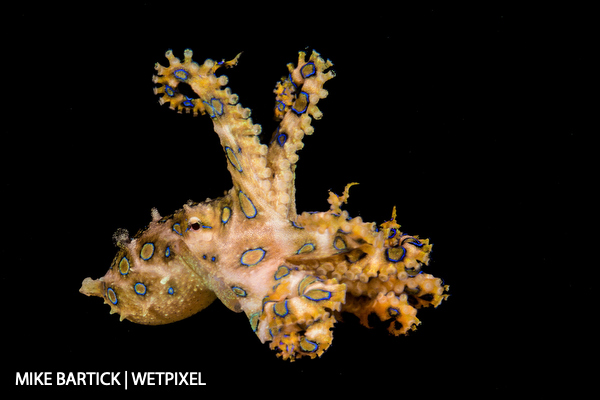

For conversational purposes, I’m going to concentrate on what I like to call the “Big Four” of octopus encounters: The wunderpuss (Wunderpus photogenicus), the mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus), coconut octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) and of course, the blue ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena sp.)

In General: A Basic Natural history for Octopuses

Octopuses are mollusks, in the same family as clams and snails. But through the different stages of time and ocean environs, the octopus has left the shell behind and has evolved to become a more sophisticated creature. Their primary food sources vary and depend primarily on their size. They will eat almost everything but like humans, tend to enjoy crabs and clams.

Their hunting techniques usually involve webbing over their subject and then “beaking down” using their hidden beak under the mantle. This hardened tooth-like beak will pierce clamshells without a hitch as well as shrimp shells and whatever else it wants. Most octopuses also possess some venom and use their beaks to pass this toxin into their prey.

The endearing octopus often has quite surprising capabilities. They change shapes, colors and textures to disguise themselves and to communicate. They can squeeze themselves into the smallest of openings, as little as their beak and can make themselves small and stealthy for hunting or enlarge themselves to deter a would-be predator.

They can survive out of water for a short period and have been seen hunting from one tide pool to the next. Many of their capabilities are still unknown and only through observation can we detect and study such behaviors. These intelligent creatures are no doubt capable of much more than we know of and certainly much more than what is listed above. ###Sexual behavior: Reproduction is the primary goal for all octopuses and continuing the lifeline is their primary mission.

The male octopus has seven arms, with arm number 8 being a reproductive organ. He uses this “short arm” to pass his sperm into the oviduct of a female in a small packet called a spermatophore. The male dies shortly after that, but the females mission has just begun. Once the packet has been received it opens with a burst; the sperm is then released and kept safe in a specific organ of the female. The female will hold onto the sperm until she feels it is time to lay her eggs. She will collect sperm from several different males to fertilize the maximum amount of eggs possible, tilting the odds of survival in their favor. At a later time, when the eggs are released, they will pass through the organ containing the sperm and fertilize the eggs, one at a time. The eggs are then laid in a strand that is often wrapped together, four strands at a time.

Where does she put the eggs you ask? Well, that all depends on the type of octopus. A giant Pacific octopus or a day octopus might lay their eggs in a den. Both species hang their eggs from the ceiling and then guard them until they hatch. The female devotes 100% of her energy to this task and will rarely if ever, leave the nest. Eventually, the females starve to death as they are unable to hunt. Others, such as the coconut octopus carry their eggs, and still, others might find whatever they can to shelter and care for their eggs. This can sometimes be a bottle or other detritus.

Once the eggs mature and hatch, the paralarvae will drift in the plankton cloud and develop into the larval stage. Transparent or slightly opaque larval octopus drift, hunt and try to avoid predation while feeding. Many octopuses will spend up to 25% of their lives in this phase. Finally, having gained enough strength to “settle” the octopus will leave the pelagic zone and take up foraging on the sandy slopes. Here the strategy changes yet again and while some (blue rings) octopuses exist in a nomadic fashion, others concentrate on making a home.

The appearance of the octopus changes yet again as it moves into the juvenile phase, becoming the octopus that we are more familiar with seeing on dive sites and leaving their transparent phase by developing pigment.

Sadly, once sexual maturity is reached and reproduction has occurred, the terminal phase is quick to follow.

Other cool octopus facts:

- Octopuses have 3 hearts

- Blood is copper-based

- Measured at the siphon

- “Passing cloud” ability to alter its appearance/texture according to the substrate

- Brown white coloration indicates a willingness to mate

- Will learn and use tools-offer them a stick or a shell

- Can regenerate arms

With all of these fantastic superpowers, most octopus encounters can go one of two ways. Either they shy away and don’t want to play, or they will be a “real player.” I recommend video capture for the best of the action when they are active. However, for still shooters, an octopus can also make a great subject to work with as long as you are calm. If you see an octopus foraging along the sand, give it a little space and allow it to hunt. Watch as they quickly navigate the sandy slope, reaching into holes or gliding over rocks. This is when a mimic octopus begins to work its magic as well.

The hardest part about shooting great images of octopus is that many times they are low to the sand or have a tendency to blend in perfectly. This is cool to see happening but not so cool when you’re trying to capture a photo.

Mimic and wunderpuss are close cousins and will often compete with each other for space. The mimic can have a black/brown and white barred appearance with elongated “horns” over their eyes. However, they can retract them. Wunderpuss tend to be a more coppery color with a mottled siphon, but the two are not always easy to tell apart.

The wunderpuss is also an “aggressive” octopus and has exhibited cat and mouse tactics with their prey, maybe to tire them out for an easy kill. The wunderpuss has also been seen and documented “strangling” other octopus. The reason is not entirely apparent, but the fact remains, these guys are aggressive.

Photo tips:

Using a snoot with a wide cast of light helps to illuminate your subject. Combine the snoot flash with a lower ISO and fast shutter speed and eliminate ambient light. Panning with a mimic as they move downslope and using a slow shutter speed is also a fun shot. The classic image is the “jolly roger” shot which to me, looks like the skull and crossbones of pirate’s flag. Snooting down on just the body with sharp eye contact is another composition that works. Remember to experiment and have fun watching these guys.

Blue ring and mototi octopus are both in a subset together and are highly venomous. Their TTX toxin is powerful stuff that is created through the digestive process. This venom is involuntarily passed through their saliva when they beak down on a subject. The TTX is also present on their skin tissue so please try to resist licking these guys no matter what.

When a blue ring hunts, the tips of their arms will be held up, and they shake them like a rattlesnake shakes its tail. They tend to be more nomadic but like other octopus, experience a short life cycle.

In common with many octopus encounters, the action is often fast and to capture the essence of how they hunt; a straight natural history image sometimes tells their story the best.

Coconut octopuses are highly resourceful and will utilize, analyze and industrialize. Using materials they find, the coconut octopus will either create its shelter or take something over to live in. It isn’t uncommon to see them in bottles or using shells to shore up the walls of their burrows.

The best action for a coconut octopus is caught on video, but for still shooters, backlighting and snooting are also great options.

For a long time, it was thought that these images were produced only if the subject is lifted into the water column. Well, as it turns out, it does occur naturally. The reason for the behavior is unknown but may be hunting, avoiding predation, drifting or looking for a female/male. The wunderpuss will leave the substrate and take to the water at times. Encouraging these animals into the water column (Editors note: Using a guide to lift and then release them or chasing them up with a camera) is highly unethical.

The wunderpuss takes on many forms, as do other octopus in their unique ways. This natural history image shows exactly what I saw, a stick in the sand or even seaweed. Once I looked a little closer I realized, Wow! That’s a wunderpuss!

Just under the boat, a wunderpuss emerges from its hole extending its arm towards me. I used my LSD snoot without the mask to capture the image. This was shot in broad daylight and shallow water. Brown subject on brown sand.

The mimic octopus gets its nickname due to its shapeshifting ability that seems to mimic other subjects. The truth of the matter is that all octopus can do this. However, the mimic appears to do it best. I’ve yet to see one mimic a lemon goby, but I’m keeping my eyes peeled for this.

A mimic will sometimes peer out from its burrow, and when it does, this means a slow approach is needed. If spooked they will vanish into the hole and wait until you are out of air before they come back out.

If you use a slow approach, you can try to gain its trust by offering it something. They love to examine shells and sticks to see if they can use them for something.

The most significant difference though is not the rings but how they live. While many of the regular blue rings live in a nomadic fashion, it isn’t uncommon to find a Mototi residing in the same place for an extended time. When I see this on a trip, I usually plan to return to that dive site properly prepared to capture a specific shot I might have in mind.

Mototi can also take on a cool striped pattern. I’ve only seen this happen briefly during an encounter or when they jet away. This one is striking the classic boxer pose that I’ve seen with many other octopuses, I’m not sure what the posturing translates to, but it sure is fun to photograph.

The most important thing about shooting behavior is of course observation, patience and giving the subject enough room to behave naturally. Once the subject is comfortable with your presence, get ready for some action. Check your settings and exposures first and don’t blow a chance of a lifetime encounter.

Further reading and reference:

Octopus, The ocean’s intelligent invertebrate / A natural history by Jennifer A. Mather, Roland C. Anderson and James B. Wood

Available on Amazon and other bookstores.

About the author:

Mike Bartick of Saltwater Photo is a professional underwater photographer who is widely published and also manages the Crystal Blue Dive Resort in Anilao, Philippines.